Local funding is a key to conservation success

November 8th, 2022

By Scott Park

This is an excerpt from the Fall/Winter 2022-2023 issue of the Upstate Advocate, Upstate Forever's twice-yearly publication. To read a digital copy of the complete publication, please click here.

You've probably heard this so often it goes in one ear and out the other, but I'll say it again: the Upstate is growing.

There are certainly upsides to the region’s popularity: jobs, opportunities, economic development. However, the negative impacts from rapid growth — overcrowded parks and trails, impacts to waterways, and vanishing farmland as a result of sprawl, to name a few — are already here.

Upstate Forever and our many conservation partners are already hard at work to protect special places that are best left undeveloped. However, the need is urgent, and time is not on our side. We must be proactive about land conservation right now. The key to accelerating land protection in our rapidly growing region is robust local funding opportunities.

What is “local funding?”

Local funding is just what it sounds like: local governments and groups designating dollars for local land conservation projects. Successfully applied local funds go directly to supporting land conservation projects and are typically separate from organizational operating budgets that include staff time and overhead. The major difference with local funding is the ability to attract greater attention from federal, state, and other large funders to support the protection of our special places. In a word: leverage.

Local funds are very versatile. Each fund is different because they may focus on different priorities or geography, but throughout the Upstate, these existing competitive funds can be used to provide matching funds to attract national and statewide grants, purchase or offset the costs of conservation easements, and/or buy fee-simple land outright.

Examples of local conservation funding sources in the Upstate include the Greenville County Historic & Natural Resources Trust, the Oconee County Conservation Bank, and the Upstate Land Conservation Fund. Additionally, in their most recent budget, Spartanburg County Council included substantial funding for land protection that provides public access. Upstate Forever applauds these counties for their commitment to preserving special places and quality of life for their residents while there’s still time.

Creating dedicated funds for local conservation increases the likelihood that land protection can happen more quickly, closer to home, and on a larger scale.

Examples of funded projects

Grant Meadow, Pickens County: A grant from the South Carolina Conservation Bank (SCCB) enabled the protection of this iconic view of Table Rock.

Upper Shoals at Glendale, Spartanburg County: Funding from the Upstate Land Conservation Fund (ULCF) contributed to the protection of 88 acres owned by the Tyger River Foundation. The property is adjacent to Wofford College’s Goodall Environmental Center and the Spartanburg Area Conservancy’s Glendale Shoals Preserve.

Chauga Heights, Oconee County: An SCCB grant to Naturaland Trust and an investment from Oconee County provided for the purchase of more than 200 acres adjacent to Chau Ram County Park. Photo by Mac Stone

Granting organizations increasingly require local funding matches.

Most importantly, local funds can be used as matching funds to help leverage conservation grants from federal, state, and private sources. Many of these conservation grantors increasingly prioritize applicants that can bring money to the table in the form of matching funds.

As an example, the South Carolina Conservation Bank (SCCB), an important and effective partner in preserving the natural resources in the Upstate and across the state, often requires a local match to leverage state dollars.

"As a statewide conservation funder, partnering with counties and other local funding sources validates conservation projects and allows state dollars to go further," said Raleigh West, Executive Director of the SCCB. "When counties participate financially in land protection projects, they are showing the Bank that it’s a priority. Local skin in the game accelerates the Bank’s financial leverage, giving those projects an automatic leg up".

"As a statewide conservation funder, partnering with counties and other local funding sources validates conservation projects and allows state dollars to go further," said Raleigh West, Executive Director of the SCCB. "When counties participate financially in land protection projects, they are showing the Bank that it’s a priority. Local skin in the game accelerates the Bank’s financial leverage, giving those projects an automatic leg up".

The availability of local funding for these matches makes Upstate conservation partners and their projects more competitive and more likely to attract additional grants from federal, state, and private sources.

Collaborative funding partnerships among multiple sources and conservation partners are also increasingly common.

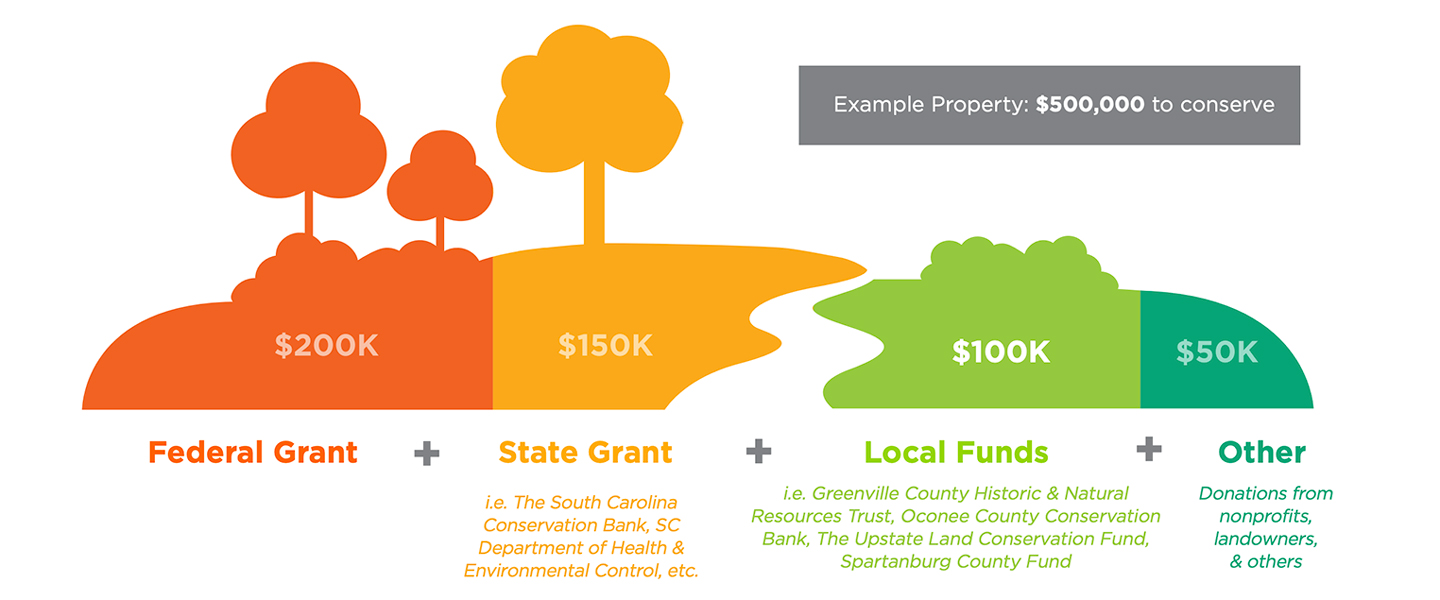

Local funds can be used as matching funds to help leverage conservation grants from federal, state, and private sources — making applications from Upstate organizations more competitive in the grant-seeking process. Here's a fictional example:

Local funds can pay for conservation easement value or offset closing costs.

A conservation easement is a voluntary, permanent legal agreement that retains the original property owner’s ownership but with restrictions — typically restrictions on development — that protect the property’s conservation values. A conservation easement is transferred much like a real estate closing. After a conservation easement is in place, the property is monitored annually to ensure the conservation values are maintained according to the owner’s easement terms.

In these cases, funding can be used to meet the need for landowners who may be interested in protecting their property but need incentives greater than potential tax benefits.

Local funds can help compensate the landowner for the diminished value that the conservation easement’s restrictions place on the property. Some monies may also be used to offset associated closing costs, such as appraisals, surveys, and legal fees.

Funds can be used to buy fee simple land outright.

A “fee simple” transaction is how property is sold to the next landowner, much like when you sell your home.

Conservation organizations are limited to paying up to the appraised value of a property. The value is determined by a certified appraiser. In these cases, successful applications to funding sources may help pay for the land and the associated closing costs.

Upstate Forever typically does not purchase land fee simple, but many of our partners like Naturaland Trust, The Nature Conservancy, Conserving Carolina, and the Spartanburg Area Conservancy do. It’s a straightforward and effective way to acquire special properties that include high-priority natural resources.

The growing local funding landscape is a great conservation model in a region well known for innovative public-private partnerships and other trailblazing capacity building.

Scott Park is the Glenn Hilliard Director of Land Conservation for Upstate Forever. If you, or an organization you represent, is interested in learning more about direct conservation funding, please contact Scott at spark@upstateforever.org.