Ecosystems Services: Why Conservation Boosts the Bottom Line

November 26th, 2018

Originally titled "The Economic Value of Protected Open Space & Local Water Resources," the following is adapted from the Shaping Our Future Growth Alternatives Analysis, which included a case study series highlighting growth-related issues that Upstate communities are current grappling with and recommendations for how to address them. The case studies were authored by Nadine Bennett working with consulting firm City Explained. Learn more about the Shaping Our Future project

Applying an economic value to the natural world seems in some ways to be a paradox. Many of us think of natural spaces as places to escape the everyday world of dollars and cents. While we typically recognize the health and quality-of-life benefits afforded by a forest walk, a favorite fishing hole or a beautiful landscape – we often fail to acknowledge the economic benefits such areas provide.

Jack Robert Photography

Not surprisingly, farmers, hunters and fishermen often intrinsically understand the value of productive land and clean water – in economic terms. With their livelihoods in some cases dependent on these resources, they have historically been some of the first to advocate for their proper stewardship and conservation.

Most past attempts, however, to assign economic value to natural areas have focused solely on resources that quickly convert to commodities, such as standing timber.

More recently, however, economists and researchers are taking a more sophisticated look at the economic value of natural areas, open space and local water resources. And some forward-thinking communities and utilities are following suit – taking action to not only preserve, but also capitalize on, the economic value these natural areas provide.

Local Economic Engines

As anyone who has visited Great Smoky Mountains National Park on a busy summer weekend can attest, the popularity of scenic places has risen dramatically in recent years. Studies have cast new light on how natural areas can serve as local economic engines for nearby communities. While this opportunity may seem obvious for communities outside national parks like Great Smoky Mountains, it is also true for other scenic destinations and publicly-accessible natural areas such as state and city parks, and greenways and blueways.

Known as “amenity destinations,” these communities often have stronger, more diverse economies – especially as compared to other rural areas. Upstate destinations such as Table Rock State Park, Sumter National Forest and Chattooga National Wild and Scenic River draw visitors from around the country. Jocassee Gorges – in Pickens County – has been ranked by National Geographic as “one of the world’s last great places”. Visitors to these destinations support the local economy, especially small businesses critical to the prosperity of smaller towns.

Upstate destinations such as Table Rock State Park draw visitors from around the country. Photo: Tommy Wyche

One of the area’s success stories is the Greenville Health System Swamp Rabbit Trail, a 20-mile trail weaving from south of downtown Greenville to north of Traveler’s Rest. The Trail was the product of a multi-year effort of a coalition of public and private resources. Once complete, the uniquely-named trail has sparked an economic resurgence as restaurants and businesses have popped up or even relocated to be alongside it.

The most recent estimates of usage suggest that over a half million people use the trail per year. An extension from downtown Greenville to Verdae – a 1,000+ acre master-planned neighborhood – and the Millennium Campus – a master-planned corporate community – is in the works. Laurens County is also planning to extend the trail into its jurisdiction, a key goal of the Laurens County Trails Association.

In nearby Pickens County, the cities of Pickens and Easley worked together to build the 7.5-mile Doodle Trail as a rails-to-trails project, linking the two communities. Also in Pickens County, the Friends of the Green Crescent are advancing a vision to better connect the communities of Clemson, Central, and Pendleton with a network of walking and biking trails – both on and off road.

There are similar efforts afoot in Abbeville, Anderson, Spartanburg, and Greenwood counties – at various stages of planning.

Despite these sorts of efforts, the benefits of rural tourism are remarkably patchy. Why do some communities near beautiful natural areas prosper while others do not?

Engaging the Business Community

Cases like the Swamp Rabbit Trail illustrate the importance of public-private partnerships. This is especially important in rural areas where small businesses and entrepreneurs make up a large proportion of the business community.

Rural areas tend to have a much higher percentage of sole-proprietor businesses than urban areas. Experience has shown that a willingness by entrepreneurs to engage, try new things and support each other are very important to successful rural tourism efforts.

For example, staff from Greenville County have proactively engaged local business owners and churches along the Swamp Rabbit Trail to offer shared parking with trail users. Well organized Chambers of Commerce and similar organizations are key.

Authenticity & Uniqueness

Visitors to rural regions tend to want specific experiences that feel authentic and unique. Destinations like the Swamp Rabbit or Doodle Trails are built on the beds of historic railroads. The names themselves catch the attention and are genuinely authentic – both are old nicknames for the trains that ran on them.

Understanding what a community has to offer and what visitors are looking for are important steps. Some local development organizations help rural communities look at themselves in new ways by identifying assets such as architecture, art, cuisine, customs, scenic destinations and history. Helping small towns recognize the value in their own communities and shifting perspectives towards wanting to share those assets are important outcomes.

Taking Action

Communities that are near beautiful natural areas do not all prosper equally. Those that do seem to take deliberate actions – finding ways to preserve what makes them special and marketing in a way that helps them stand out.

The Spartanburg Convention and Visitors Bureau focuses on five themes which illustrate this trend well: culture, history, agritourism, recreation and products made in Spartanburg. They conducted a Tourism Action Plan and Feasibility Study with funding from a Rural Business Enterprise Grant.

They identified goals, target audiences and strategies that played well to the county’s strengths. This led to new advertising materials and a modern, multifaceted outreach campaign. The results of the efforts have borne fruit: people are staying longer and spending more in Spartanburg.

Ecosystem Services

In the last century, researchers have coined terms such as “natural capital” and “ecosystem services” – generally defined as benefits that people receive from the healthy and often complex systems found in the natural world.

These services are not just luxuries, but rather, are vital to life on earth. Additionally, when not provided by nature for little or no cost, these services must be provided through other – often costly – means.

For example, we know that deforesting watersheds negatively impacts water quality, making it more difficult and expensive for utilities to treat for human use.

Conversely, protecting land surrounding drinking water intakes is a strategic investment to reduce treatment costs down the line and deliver high quality water to customers. Greenville Water, for instance, boasts that its water is exceptionally pure because the land around it is protected.

The utility owns, manages and protects 26,000 acres in two watersheds that feed the reservoirs from which some of their drinking water supply is drawn – a visionary approach to water quality treatment implemented decades ago by forward-thinking leaders.

Other Upstate utilities have begun working more recently in partnership with local land trusts, private landowners and others to utilize voluntary land protection as a proactive means to encourage stewardship of soil and water on private lands in strategic locations.

Mapping The Impacts of Development

When land is converted from fields and forests to urban development, any ecosystem services that were once being provided by that land are lost. Though it is difficult to quantify these types of benefits, recent advances in the field are making this kind of research more accessible.

One software program known as InVEST – developed by researchers at Stanford University – are helping communities across the globe better understand which lands within their jurisdictions naturally provide essential functions such as providing high-quality habitat or sequestering carbon.

Similarly, InVEST can highlight which lands – if developed – would likely cause the most damaging impacts to water quality. Such information can be provided to local utilities, local governments and others to enable more strategic investments in land protection and to inform future land use planning and decision-making.

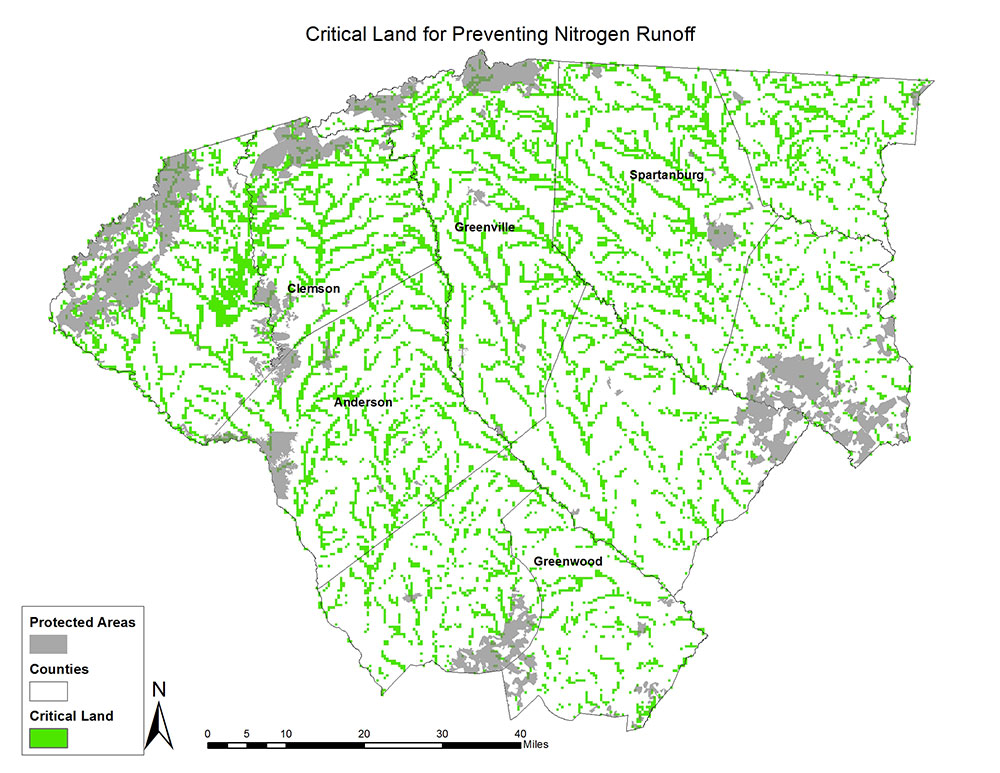

An example of an InVEST GIS layer showing the most critical lands in terms of nitrogen runoff

In the Upstate, Dr. John Quinn and his students at Furman University are using InVEST to quantify and map benefits provided by currently undeveloped lands across the Upstate region. As part of the Shaping Our Future project, the Furman researchers examined the degree to which undeveloped lands in the Upstate provide value in terms of water quality protection, high quality habitat and carbon sequestration. They forecasted how those lands would be impacted assuming each of the four growth scenarios that were compared as a part of the growth alternatives analysis.

Not surprisingly – in large part due to the massive amount of land consumed – the Trend Scenario produced the least favorable outcomes in every case. In other words, the InVEST model predicts that if Upstate communities continue on their current growth trajectory, they stand to lose the greatest amount of value currently being derived from natural areas as related to critical habitat, carbon sequestration and water quality protection.

Fortunately, many impacts from land use change on ecosystem services can be mitigated with thoughtful planning. Leaving vegetative buffers along streams, thoughtfully managing timber and agricultural lands, and strategic land protection can go a long way towards mitigating the impacts of development on ecosystem services.

A recent application of this innovative modeling software is the development of an Upstate Critical Lands Map. Through a partnership of Upstate Forever, Furman University and Pacolet Milliken Enterprises, the region’s most environmentally sensitive lands in regards to water quality and high quality habitat have been identified and mapped.

Other factors such as adjacent protected lands, historic sites and drinking water sources also helped pinpoint these special places. Upstate Forever will use the results of this work to guide future land protection efforts and provide local Upstate governments important data to inform future comprehensive planning and land use policy decisions.

Oconee Forever

Guided by local citizens, Oconee Forever supports initiatives to conserve and enhance the quality of water and watersheds, forests, wildlife habitat, rural areas, working farms, scenic vistas, and historical sites in the county.

Oconee Forever’s origins were inspired by the fight to preserve Stumphouse Tunnel, near Walhalla. The tunnel was first proposed in 1835 as part of a new route between Charleston and the Ohio River Valley. By the late 1850s, South Carolina had spent over a million dollars on the project, but the State was unwilling to spend more, and the project was abandoned, leaving a partially completed tunnel.

In 2007, a developer attempted to purchase the property from the City of Walhalla, but eventually, a consortium of non-profit conservation groups, private individuals, and the state raised the money to preserve the area for public use.

Today, the tunnel is part of a 439-acre preserve that includes some of the most important and celebrated natural and historic landmarks in the region. Stumphouse Mountain was saved through the combined efforts of Oconee Forever, the South Carolina State Conservation Bank, and additional private and public funds and stakeholders.

Oconee Forever’s efforts are accomplished by advocating at County Council meetings, supporting conservation-related initiatives, educating private landowners on voluntary options for conserving their land, and using fundraisers as a way of highlighting the importance of conservation in the area.

One of group’s biggest successes was helping establish the Oconee County Conservation Bank (OCCB), a local government agency created to provide grants to landowners who wish to conserve their land in perpetuity. Oconee Forever was instrumental in passing the 2011 ordinance that created the bank. Duke Energy donated $618,000 to the OCCB as part of a 30-year relicensing agreement recently signed for the Keowee-Toxaway Hydroelectric Project. The OCCB is now ready to provide their first grants.

Advocacy for conservation causes can be difficult in Oconee. While polls indicate the local population greatly values the environment and protection of natural resources, there is also resistance to government-led conservation efforts, and conservationists often face criticism and skepticism. Oconee Forever encourages and motivates participation by “pro-conservation” residents in political and community processes.

Oconee Forever’s annual event targeting larger landowners raises awareness of conservation easements/agreements. Oconee County now has the third highest number of conservation agreements in the Upstate, following Greenville and Spartanburg Counties.

Conservation agreements are voluntary contracts signed by the landowners that limit the future uses of the land. Uses that do not interfere with the conservation value of the property – such as maintaining a family residence, adding limited new residences, farming, fishing, hunting, and timber management – are generally allowed, while commercial, industrial, and residential subdivisions are not. Conservation agreements ensure that properties remain in their current state. If the land has significant historic or natural resources, federal and state tax incentives are possible.

Through their efforts, Oconee Forever encourages locals to become involved with current initiatives in the County and enables them to take direct actions to preserve their land.